As much as one-third of our food supply depends on pollinators like insects and birds that fertilize plants when they fly between blossoms.

But moths, one such pollinator, get confused by urban fumes like car exhaust, which keep them from finding the flowers they feed on, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Washington and the University of Arizona.

Observing The Moth's Flight Patterns

In a cluttered basement laboratory at UW, assistant biology professor Jeff Riffell uses a big fan and a wind tunnel made of plastic sheeting to study the flight patterns of moths.

“It allows us to simulate the wind conditions that these insects are flying in in nature. So it provides a really controlled environment to see these animals fly in,” Riffell said.

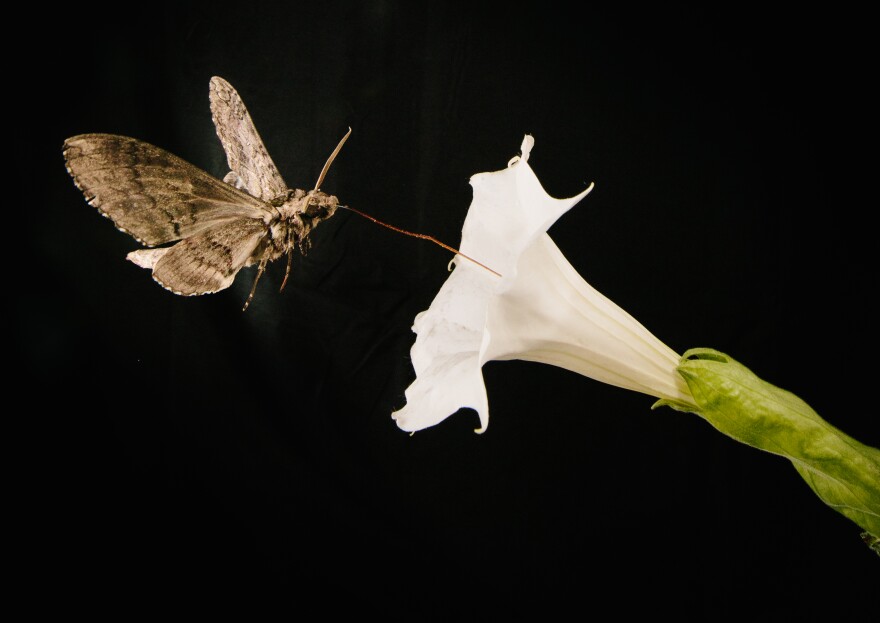

Riffell’s focus is on a moth called Manduka sexta, also known as the tobacco hornworm moth. Most have wingspans that are 4 inches wide.

“It’s this giant, very beautiful moth that you’ll see if you’re in the east part of the state, You’ll see it flying around in the early evening, and you’ll think that it’s a humming bird, it’s so large,” he said.

The tobacco hormworm moth uses a keen sense of smell to find and feed on the fragrant nectar of certain flower blooms.

‘A Stumbling Drunk Version Of Flight Tracking’

Using video recorders, electrodes inserted into the moths’ antennae and an odor delivery device, the researchers documented the effects when they introduced different smells into the wind tunnel.

Riffell says when they added only the flower scent, the moths tracked to it straight as an arrow. But when they added pollutants such as car exhaust, the moths got confused.

“They’re kind of doing a stumbling drunk version of flight tracking. They sense the flower a little bit, but they actually can’t really locate it and they don’t know precisely where it is,” he said.

Riffell says air pollution levels in Seattle neighborhoods like Phinney Ridge and Ballard were high enough to significantly decrease the moths' ability to find the flowers.

The findings were published in the journal Science. Riffell says his team is eager to expand on the research, and see whether fumes also affect honeybees. He says it could provide insight into whether urban emissions could affect pollinators in farms near urban centers.