It was a hot August morning – the height of summer vacation – but two classrooms at Edison Elementary in Centralia were abuzz with activity.

In one room, kids were studying the mechanics of flight, using Dixie cups, tissue paper and masking tape to create designs for something an aerial photographer could use to float down from the sky and take pictures. Their teacher, Brian Bartel, timed how long their creations stayed airborne.

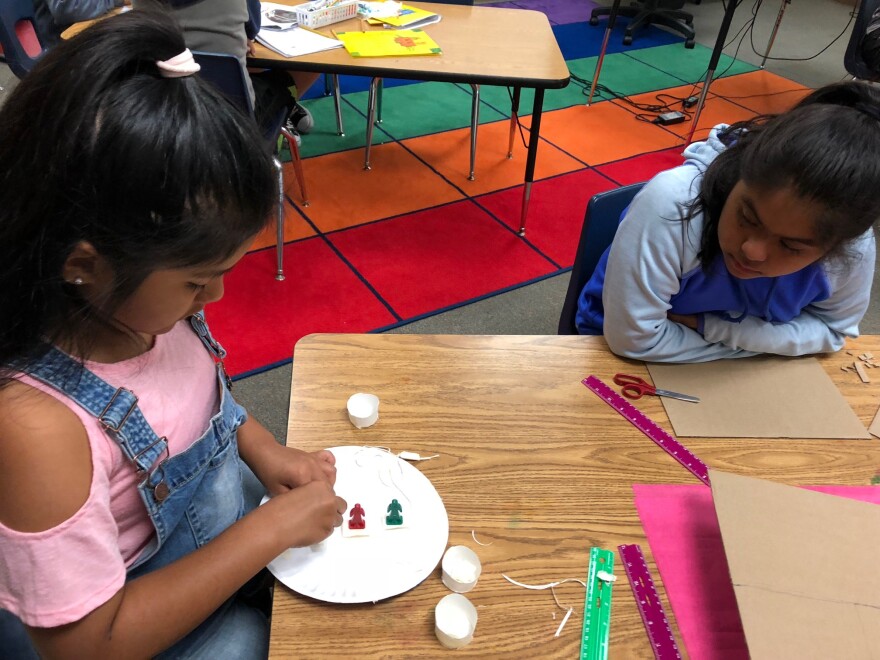

And in another classroom, a group of first and second graders assembled water filters with screens, cotton balls, pebbles and cheesecloth to try to filter water contaminated with soil and tea leaves.

The students are all children of migrant workers employed in the agriculture or fishing industries. Centralia has offered a summer-school program for migrant students for the past three years, part of the federally funded migrant education program created as part of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

Program Origins

Part of the impetus for creating the federal migrant education program was a 1960 documentary by journalist Edward R. Murrow called Harvest of Shame that helped draw attention to the abysmal living conditions of migrant farmworkers. Many earned about $1 per day. Families lived crammed into one room and then hit the road as soon as one crop had been harvested, driving hundreds of miles to other parts of the country to pick other crops.

And the children often didn’t go to school.

In the documentary, one migrant farmworker with nine kids said in an interview that her older daughter probably couldn’t continue to go to school because of financial pressures.

“Of course she’d probably be like the boy and have to quit as soon as she’s old enough,” the mother said. “She really likes to go to school but she had to miss last week because she had to keep the baby for me to work.”

Creating a special program to help improve educational opportunities for migrant children was also important to President Lyndon B. Johnson, who signed the law.

Before he ever got into politics, Johnson taught for a year in a school in South Texas. His students were Mexican-American children of farmworker families who were very poor. So when Johnson signed the law creating Title 1 programs and directing federal dollars to provide a better education to low-income kids and migrant children, it was really meaningful to him personally.

“As a son of a tenant farmer, I know that education is the only valid passport from poverty,” Johnson said at the bill signing in April 1965. “As a former teacher, and I hope a future one, I have great expectations about what this law will mean for all of our young people. As President of the United States, I believe deeply no law I have signed or will ever sign means more to the future of America.”

Since then, the program has had staying power through nine administrations – both Democrat and Republican.

Helping Kids Whose Families Move

The aim is to ensure that children receive academic support so that they can make similar progress in school as their peers, even if their families have to move because of the nature of working in agriculture or fishing.

To qualify, students have to have moved in the past three years and have a parent working in agriculture or fishing.

Ten-year-old Yessica is going into fourth grade and moved to Centralia with her family from Texas about a year ago.

She said one hard part about moving has been “meeting new friends and trying not to be shy.”

Yessica’s two younger brothers are also in the summer program. Amanda Ramírez, her mother, said she thinks it’s great they have this opportunity.

Instead of being at home watching TV or sleeping, they get to learn, she said.

Her oldest son, Axel Mejia, who’s going into his senior year of high school, got to visit the University of Washington for a week, also through the migrant education program.

He said it made him envision studying there.

“Honestly, I’m going to work hard this senior year,” he said. “It actually did make me want to go there.”

His dad works at a poultry farm. When they lived in Texas, Axel said his parents did janitorial work and brought him along when they cleaned at night. He started helping them around age 6.

“For example, I had to clean toilets. I had to do a lot of things that many people kind of see as like, 'Ooh, why are you doing that?’” he said.

Axel said he wants to go into fashion or design and knows it’s important to his parents that he pursue his dream job.

Challenges In School

But school can pose challenges for migrant children. Statewide, less than a third of migrant kids passed the 8th grade English language assessment. Less than one fourth passed the math test.

“Just moving around, every time you move, you’re interrupting your education,” said David Eacker, director of state and federal programs for the Centralia School District. “It sets you farther behind. You’re learning new systems, new people, you’re losing your friends, you have to make new friends, so there’s quite a few challenges there.”

Centralia has about 130 migrant students. Overall, Washington state has the third-biggest migrant education program in the country with almost 30,000 kids.

This year, the state’s getting $27 million in federal funds for it. That pays for recruiters to identify students and educators to offer extra academic help.

There’s also a requirement that districts have parent advisory committees. The program is not specifically aimed at immigrants, but there is a lot of overlap because there are so many immigrants working in agriculture.

Eacker said it’s been a little hard to get parents to come to meetings lately.

“This last one we had some food there, it was specifically for migrant families and those families didn’t show up,” Eacker said.

He said he thinks that may have to do with people being afraid of the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement.

Summer Science Class

But families still sent their kids to the summer school. In Bartel’s class, the children tested out their creations in a wind tunnel to see how long they can stay aloft.

Bartel said he likes to lead this class because it’s so hands-on and it’s fun when the students build something that works.

“Their eyes just brighten up a little bit, so as a teacher, it’s always cool to see that,” he said.

Amanda Ramírez said she’s grateful her kids get to go to this class in the summer. To her, education is the most important thing. It’s key for her kids to be able to get whatever job they may want, she said.

Making sure the children of migrant workers have the same educational opportunities as other children is what President Johnson envisioned more than half a century ago.