Editor's Note: This is the second installment of a two-part series. Learn how scorpion vemon led local researchers to the brink of discovery of a new class of drugs in Part 1.

Consider the chemical elegance of a potato. Or a petunia. Or a horseshoe crab.

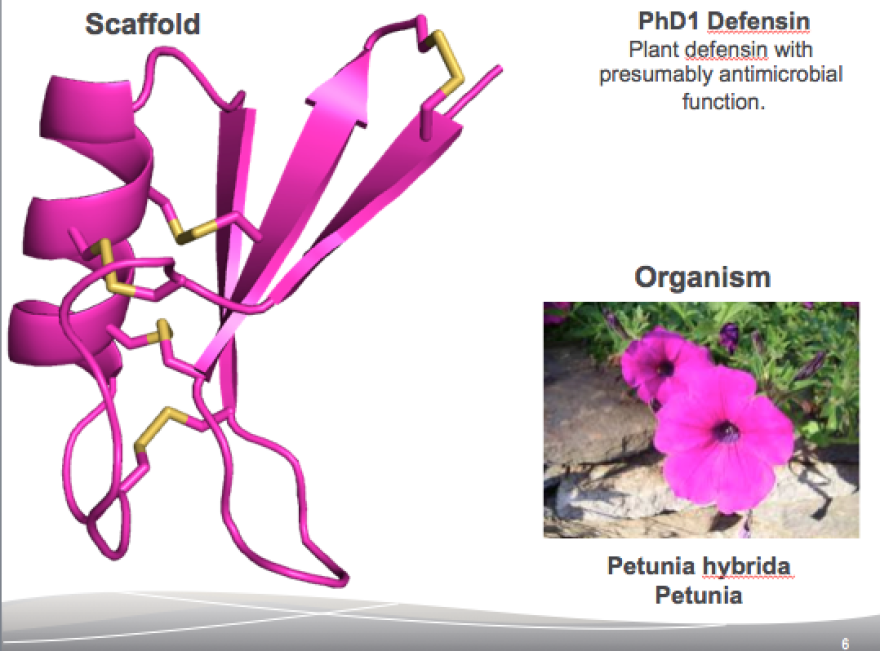

Somewhere in each of those organisms is a special little protein uniquely equipped to do what medicines do: barge in on biological processes and mess with them. With a little tweaking, it’s possible they could be trained to, say, keep cancer cells from spreading.

A few years ago, Dr. Jim Olson and his team at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center had figured out how to make those proteins by the thousands, but they hadn’t yet figured out how to pay for it.

“While we don’t need huge money in terms of drug discovery, it’s just nearly impossible to get it through traditional grant mechanisms at the stage that we’re at,” Olson said.

Olson hopes the work will lead to a whole new class of drugs. The project holds a lot of promise, but also enough risk to make big funders hesitate.

And yet ordinary people seemed to connect with Olson’s research. It helped that his molecules come from intriguing sources like scorpions, spiders and sunflowers. And so his team came up with an idea.

“We thought it would be really interesting if the community could adopt these drug candidates, and follow them through and cheer them on as we try to advance them toward improving the lives of people with cancer or brain diseases,” Olson said.

Project Violet

This was the birth of Project Violet, which was named after a vivacious 9-year-old girl that Olson treated. She knew she would not survive her brain cancer, and she asked to donate her tissue to researchers so scientists could help other sick kids. Violet’s generosity inspired Jim Olson to channel the kindness of others.

Crowdfunding platforms have made it possible to put your money behind a short film, a candy business or a taxidermy project. Now, through Project Violet, donors can also support work to cure cancer or treat autism.

Olson’s team hopes to raise about $3 million a year. Since launching in April, they have brought in enough to hire two full-time scientists. People can donate as little as $100, and choose a molecule to adopt. They can get to know it, print up a picture for the fridge and, of course, give it a name.

A Molecule Named 'Eliza'

Olson said many people are inspired to adopt because they have lost friends or loved ones to diseases. When Steve Brooks heard about Project Violet, he thought back to a close friend who got skin cancer at age 32.

“So that was in September [or] October, and in the third week of January he passed away. It was very, very quick,” Brooks said.

Brooks does engineering work on buildings, including at Fred Hutch. That’s where he learned about the project and decided to adopt several molecules. He pulled up the website, plopped his 3-year-old daughter Eliza in his lap, and began scrolling through images of proteins and their sources.

“The scorpion the spider, the potato, and then, of course the one she focused on, the petunia,” Brooks said.

When it came time to name his molecules, the petunia protein became “Eliza.”

“It was really neat to get her to know where medicine comes from," Brooks said.

The Inside Track

Steve Brooks already has an intimate connection with this research. And now Project Violet is giving him an even closer link to what’s usually a closed-off process.

Drug discovery normally happens at big drug companies that jealously guard their intellectual property. But Brooks gets to keep tabs on his molecules and even communicate with the researchers. And since he’s got an in at the Hutch, he gets a front-row seat.

In the lobby of the Thomas building, project co-director Colin Correnti greeted Brooks, and showed him upstairs to meet the team and the proteins.

The scientists showed Brooks their representations of the molecules which look like modern sculptures of twisting ribbon and spaghetti. They explained how they construct them and make thousands of variations, looking for one that works.

A Science Experiment Wrapped In A Social Experiment

Lest he get too attached to his little proteins, Brooks got a sobering reminder. The molecules he’s named — after his daughter, his wife, his dog, a Chevy Chase character — are just a few among tens of thousands. Co-director Chris Mehlin said the vast majority will be dead ends.

“Drug discovery is the process of throwing a lot of stuff away,” he said.

And how likely is it that one of Brooks’ molecules will make the cut?

“Uhhh, do you want really the answer to that?” Mehlin laughed. “Its great-great-great-great-great granddaughter might become a drug, but the odds of one of your things becoming a drug? Very remote.”

Brooks said he’s OK with playing a small part in a long game, especially when it comes with this kind of access.

“The fun and appealing part of this whole process is just to see behind the curtain a little bit. What’s behind the big brick walls at Fred Hutch?” Brooks said.

For lead scientist Olson, that’s part of the value: demystifying the whole business of discovering new medicines. He plans to make it even more accessible by allowing classrooms of kids to adopt and follow molecules, and maybe even figuring out a way to keep score.

Trying to create therapies from scratch is fundamentally uncertain, both in terms of the science and the money. But Olson and his team hope by wrapping this social experiment around the science experiment, they can find new medicines and a way to bring almost anybody onboard for the hunt.