You're an NPR reporter covering a presidential candidate. Serious stuff, even if it's still early in the election season. As he speaks, you think you hear the candidate say something that negatively singles out African-Americans. You try to get an explanation from the candidate after he finishes, but can't get to him. So, you go back to your hotel and listen to the tape. You're convinced he said it. But it's a little garbled.

What do you do?

In the balance, as you prepare your story, could be the fate of one man's presidential candidacy, or an increase in racial friction during an election year—or just simple accuracy.

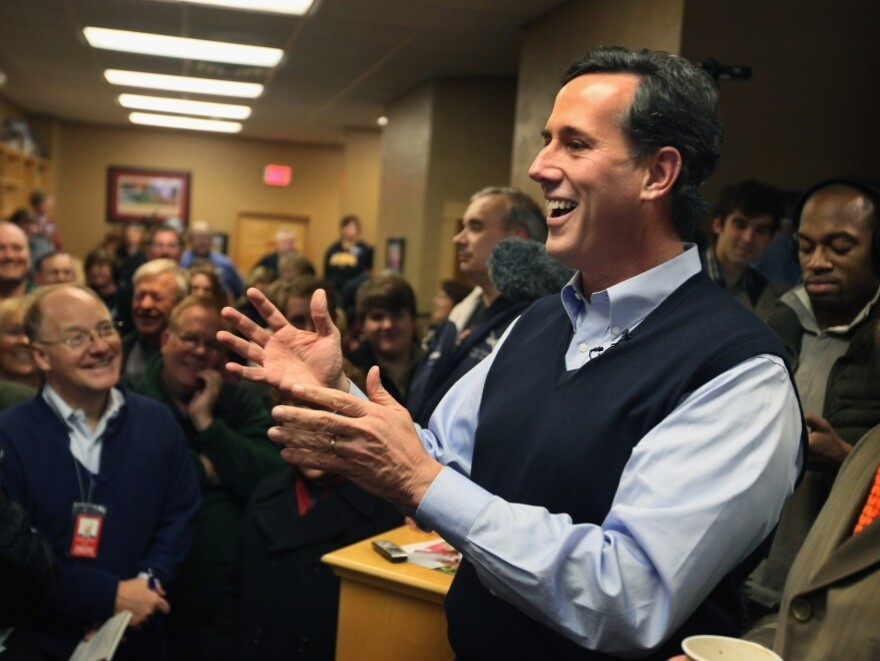

This is the situation that Ted Robbins faced covering Rick Santorum in a meeting with voters in Sioux City, Iowa, two days before the Iowa caucuses earlier this month. Unable to get an explanation from Santorum, Robbins went with what he heard, which was a slur against black Americans. Since then, however, many listeners—and the candidate himself—say that in the garbled comment, the candidate did not mention blacks. At the most, others say, the candidate might have started to say "black" but stopped himself.

All of this raises questions about how far a reporter and NPR should go to be fair and responsible. There is no totally satisfactory answer.

If someone in the chain heard what many of us did, they should have stopped a dangerous "gotcha" moment.

Sides have lined up as the story has set off a chain of accusations, claims and denials among advocacy groups, African-Americans, commentators and talk show hosts.

The issue still dogs Santorum in the blogosphere as he campaigns in the South Carolina primary.

This is what Robbins' story quoted Santorum as saying in Iowa:

They're [undefined who, but probably government and politicians] just pushing harder and harder to get more and more of you dependent upon them so they can get your vote. That's what the bottom line is.

I don't want to make black people's lives better by giving them somebody else's money. I want to give them the opportunity to go out and earn the money.

Santorum stumbles on what appears to be the word "black." You can listen to it yourself here and watch CBS' tape of that part of the speech here.

Robbins was at the coffee shop event in Sioux City with producer Sam Sanders. He said that the two of them looked at each other after Santorum finished speaking and said, in Robbins' words, "Did you hear what I heard?" It was Sanders who attempted and failed to get through to Santorum, who left quickly, Robbins said.

He continued, "We went back to our hotel. It had sounded like a Freudian slip. Then we heard it on tape and that was when we were surprised that it was as clear as it was."

Sanders agreed. In fact, Robbins and Sanders were so sure, Robbins told me, that their concern was not whether Santorum said it or whether it was racially explosive, but whether it was factually fair on Santorum's part to single out blacks. "It was factually inaccurate, and that was what bothered me, or bothered us," Robbins said.

CNN's Anderson Cooper was tendentious and the NYT's Charles Blow was sarcastic as the report took on a toxic life of its own.

Robbins said he believed that more whites than blacks receive welfare benefits. Santorum had mentioned Medicaid as part of the same rambling comment. There were few people to call on a late Sunday afternoon, and so Robbins said he searched online about Medicaid usage by race but couldn't come up with anything definitive because of the way the statistics are kept.

Neal Carruth, the supervising editor for election coverage, entered the picture and heard the tape while it was being edited. He, too, agreed that Santorum had singled out blacks. And like Robbins, Carruth said he did not frame the story in racial tinderbox terms.

"We were doing a daily from-the-trail story on Rick Santorum and his remark about black people getting other people's money was just one element of that story," Carruth told me. "It wasn't the central focus of that story, but it seemed to us a newsworthy comment and worth including."

And so the resulting story on Morning Edition did not lead with the "black" comment or hype it by calling it racially provocative. It was only midway through the three-and-a-half-minute report that Robbins said on air:

For Santorum, that [core message] means cutting government regulation, making Americans less dependent on government aid, fewer people getting food stamps, Medicaid and other forms of federal assistance - especially one group.

And then followed the tape of Santorum making the famous quote, which we could all hear for ourselves. The story then cuts back to Robbins, who adds:

Santorum did not elaborate on why he singled out blacks who rely on federal assistance. The voters here didn't seem to care.

This last comment can be taken in many ways, but Robbins says he was referring to the lack of reaction in the almost all-white audience, which clapped politely.

Curiously, many reporters were at the event, and only NPR reported the highly newsworthy black quote.

Had it been Mitt Romney, or, say, President Barack Obama, who had muffed a line, their press spokespeople would have been all over the journalists to correct—or spin—the statement. Santorum, however, has been running such a shoestring campaign that, as the Associated Press reported last December, Santorum largely moved around Iowa with just a driver and a borrowed pickup truck. It was only four days later, as he was hustling to play catch-up in New Hampshire, that Santorum said he finally had time to review the video tape of that coffee shop event.

If they had had a doubt, the NPR team should clearly have held off until confirming it with Santorum. But Robbins and Carruth said that they did not have a doubt. It was like reporting on any speech: the speaker said it, you report it. It was just one more daily story that rounds out the picture of a candidate.

Many more whites receive welfare assistance than blacks, though the proportion of blacks is higher.

Seen that way, the story was straightforward and fine. Its limitations—not getting the truth on welfare usage or more explanation from the candidate—were correctly acknowledged. This was done in the line, "Santorum did not elaborate why he singled out blacks." Robbins says that in retrospect, he wishes he would have added that they tried to get an explanation from the candidate but couldn't. This more explicit disclaimer would have been better, though only marginally so.

This entire analysis, however, relies on Santorum having said "black." It changes if you think that the journalists at NPR should have been less certain about what he said, given the garble as he spoke. The analysis changes even more if you think that not just factual accuracy was at stake, but also the demonizing of a race—blacks are taking other people's money—and the stoking of racial tension. If you think these things—as I do—then it should have been the responsibility of someone in the editorial chain of command to stop that part of the story before it ran and ask if this wasn't an unfair and potentially dangerous "gotcha" moment.

Robbins is an experienced reporter. He is based in Arizona, however, and through no fault of his own was covering Santorum for the first time. He said he did the normal background research on the candidate. A more seasoned follower of Santorum might have known that he doesn't have a history of playing the race card. This knowledge would have been a tip-off to be extra cautious.

A second tip-off was the context. While Anderson Cooper on CNN much later—and somewhat tendentiously—found that the context of Santorum's comments supported the idea that the candidate meant to say "black," I don't see this contextual inference at all.

Immediately before the comment in question, Santorum said the government or politicians are trying to get "you"—his mostly white audience—dependent on welfare. The meeting was not a white resentment affair with speakers railing against minorities.

I can't condemn the journalists for reporting what they say they heard.

In fairness, however, I have to add that Santorum is such a confusing, undisciplined speaker that the context and meaning of his comments are often hard to follow.

After the NPR story aired on a Monday morning, CBS.com did a similar short story Monday afternoon, and then followed up on the Evening News with an interview of Santorum by anchorman Scott Pelley. The anchor asked the candidate why he singled out African-Americans on welfare. You can decide for yourself whether you believe Santorum's reply that he couldn't remember what he said.

You might first ask yourself, though, if this has ever happened to you. It has to me. Few of us, additionally, have had to speak off the cuff in a forced campaign march as much as Santorum has. In Santorum's reply to Pelley, he did summarize what has been his historical position on welfare. Here is his full reply:

I've seen that quote. I haven't seen the context in which that was made. Yesterday I talked for example about a movie called, um, what was it? 'Waiting for Superman,' which was about black children and so I don't know whether it was in response and I was talking about that. Let me just say that no matter what, I want to make every lives [sic] better. I don't want anybody—and if you look at what I've been saying—I've been pretty clear about my concern for dependency in this country, and concern for people not being more dependent on our government, whatever their race or ethnicity is.

CBS was able to do a fact check. Instead of looking at Medicaid, CBS looked at food stamps, a program much easier to analyze. Pelley pointed out that only nine percent of Iowans who receive food stamps are black; 84 percent are white—somewhat reflecting Iowa's overall racial makeup.

Pure objectivity doesn't exist. It must be tempered with fairness, with context that considers consequences, or we lose trust.

Nationally, according to the Department of Agriculture, the percentage of food stamp recipients who were black was 22 percent in 2010. This is larger than their 13 percent proportion in the population, but much less than the 34 percent of food stamp recipients who were white. Seventeen percent were Hispanic.

With CBS reinforcing NPR's take on what Santorum said, the story bloomed online and on Fox News, where different interviewers asked Santorum what he meant. The candidate's replies evolved to become that he didn't say black, but he didn't say what else it was that he said. Finally on Thursday, he told John King of CNN:

I've looked at that quote. In fact, I looked at the video. In fact, I'm pretty confident I didn't say black. What I think, I started to say a word and then sort of changed, and it sort of—blah—mumbled it, and sort of changed my thought.

By now a number of advocacy groups had weighed in with angry statements condemning Santorum. "Sen. Santorum's targeting of African-Americans is inaccurate and outrageous, and lifts up old race-based stereotypes about public assistance," said Benjamin Todd Jealous, president of the NAACP. "He conflates welfare recipients with African-Americans, though federal benefits are in fact determined by income level."

Santorum's vague denial didn't help. New York Times Op-Ed columnist Charles Blow, for example, dismissed it with unbecoming sarcasm:

At first, [Santorum] offered a nondenial that suggested that the comment might have been out of context. Now he's saying that he didn't say "black people" at all but that he "started to say a word" and then "sort of mumbled it and changed my thought."

(Pause as I look askance and hum an incredulous, "Uh huh.")

What began as a few seconds in the midst of an ordinary NPR campaign story had taken on a toxic life of its own. And yet....and yet it's entirely possible—maybe even likely—that Santorum is telling the truth.

That Santorum took so long to make the denial is immaterial. There could have been many reasons for that, not the least of which was that he was busy playing catch-up to compete in the New Hampshire primary.

Among the many independent judges who don't hear the word "black" are Atlantic senior editor Ta-Nehisi Coates, Washington Postmedia blogger Erik Wemple, and NPR diversity vice president Keith Woods. I heard "black" on the first hearing, but not afterwards. But then, many other people hear "black," just like the NPR team did.

Maybe I'm too sensitive. Santorum, after all, survives. The nation's great racial divide recedes.

There is a middle ground, and if you have watched the video, many of you may be there. It is that Santorum started to say "black" and pulled back. This is partly supported by his own explanation that he said "blah" and then changed course. There is no way for us to know why he might have started to say "black," if he did. The important thing to me is that if he stopped himself, or misstated himself, then I believe that he deserves some benefit of the doubt, given his history, the context and the potential consequences of a statement that amounts to race baiting.

Adding to the tinder is a Republican primary environment in which some candidates and some far-right groups have indeed stoked racial resentments. Some Americans have faulted Santorum for demonizing two other groups—gays and immigrants—but those are separate issues.

Robbins maintains that it is not a reporter's place to guess what a candidate is thinking. He also said that he was not trying to catch Santorum in a "gotcha" moment, and I believe him. "Maybe it was a mistake, but it was his mistake, not ours," said Robbins.

His is a defensible position. If journalists start making exceptions for what they think someone meant, where does it stop? Many journalists will be uncomfortable with my emphasis on such subjective matters as fairness, benefits of the doubt, and consequences. They will maintain that neutral objectivity rules: Just the facts ma'am. And let the chips fall where they may.

But most of us know that pure objectivity doesn't exist. Reporters and editors must try to be as objective as possible, but objectivity must be tempered with fairness, and must have a context that considers consequences. This doesn't mean pulling punches. But hiding behind objectivity without fairness fuels an image of journalistic arrogance or disregard for the actual truth. Trust in the press is undercut in the process.

I can't condemn the journalists for reporting what they are convinced they heard. I am only sorry that someone else in NPR didn't hear what so many of the rest of us have heard, or didn't exercise more caution, especially when it comes to a racially sensitive matter.

There was one more curiosity linked to this convoluted story. Although many commented at the bottom of the web version of the story, only one listener wrote directly to NPR to complain. This may suggest that I am being overly sensitive. Santorum and the Republic, after all, will survive, and the nation's great racial divide will likely continue to recede. I look forward to your responses with great interest.

More from the Ombudsman:

Rick Santorum's Google Problem Becomes The StoryWe've Been Misled! No One Won Iowa!

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.